Cultural background is often an important key to understanding the New Testament. We know that many aspects of the Jewish and Roman cultures in the time of Jesus shed light on details in the Gospels, especially. So what does that kind of information tell us about the prayer or prayer outline (Matthew 6:9-13; Luke 11:2-4) Jesus gave his disciples: the Lord’s Prayer?

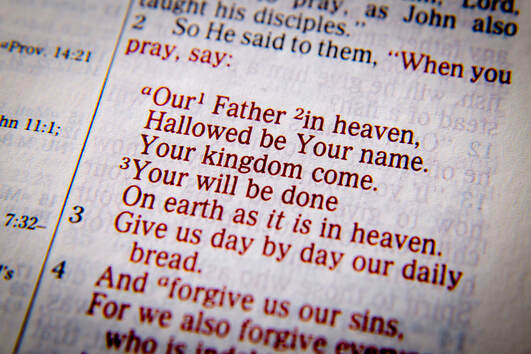

Perhaps the first things we notice when we look at the Lord’s Prayer compared to the prayers of the time of Christ are the many differences! Jesus prefaced his instruction on prayer by saying that the Gentiles prayed with a lot of words (Matthew 6:7-8), and that was certainly true of the Romans who ruled first century Judea. When Romans formally spoke or prayed to the Emperor, they often used all thirty or more of his titles. Jewish prayer could be extensive, too. The Jews used six titles of God in daily prayers – the main one being “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” By contrast, Jesus taught his followers to address God simply as Father. A side note here, but another important difference, is that in the Old Testament, “father” is used a number of times of God. But it is always a descriptive – used either as a simile or a metaphor – never a term of address.

The Jews prayed three times a day, often utilizing the “shema” of Deuteronomy 6:4-5 and other scriptures and a prayer structure involving eighteen benedictions or blessings consisting of (1) three blessings of praise, (2) twelve petitions, and (3) three concluding blessings of thanks. Once again, Jesus simplified prayer for his disciples, with seven simple requests.

Despite these differences of approach, there are a great many similarities between the Lord’s Prayer and those of the culture of the time. Some of the introductory phrases are similar to those of contemporary Jewish prayers; both mention the kingdom of God; and the request for daily bread occurs at about the same place in the middle of both Jesus’ prayer guide and the contemporary prayers of the Jews.

Nevertheless, the differences between Jesus’ prayer and those of the culture in which he lived are more noticeable than the similarities and show the truly unique aspects of Jesus’ prayer. One such distinctive aspect of the Lord’s Prayer is that of the implied responsibility that it places on the one praying regarding the petitions being made. Each petition asks for an act of God that presupposes our own participation in fulfilling the request.

Petitions – implied responsibility of the petitioner

Hallowed be your name – we must not dishonor it.

Your kingdom come – we must work for it.

Your will be done – we must strive to fulfill it.

Give us this day our daily bread – we must work for it.

And forgive us our debts – we must forgive others.

Lead us not into temptation – we must not follow after it.

But deliver us from evil – we must do what we can to escape it.

The participation of the petitioner in the various requests of the Lord’s Prayer may only be implied in the wording for the prayer, but its context – at least in Matthew – clearly shows the responsibilities of the disciple in all of the areas of petition. This is perhaps the greatest difference between the Lord’s Prayer and those of the Jewish people of the time. Cultural background shows a number of clear parallels between the two approaches to prayer, but the differences are major and significant.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed