|

We are pleased to be adding the audio book format to the available options for the free Christian books we offer! Now you will be able to download and listen to our free books in the .mp3 file format that can be played on any computer, tablet, or smartphone. We plan to release audio book titles each month and to have all our books available in this format as soon as possible. Our first audio offerings are already available – Seven Promises from the Words of Jesus; A Brighter Light: Seven Simple Steps to Help Your Christian Light Shine; and The Centurions – new and already very popular books by R. Herbert. Click on any of these titles to download the free audio book and enjoy it as you commute, relax, or as part of your devotional study.

The Bible's Book of Proverbs is often said to represent a collection of “human wisdom” and is frequently regarded as a book of practical rather than spiritual insights expressed in short, catchy sayings. Yet this viewpoint vastly underestimates the book. The value of Proverbs can be seen in the degree to which Jesus and the apostles quote and echo this remarkable book – some thirty-five times. Jesus not only quoted the book directly, but it appears to have connections to even some of his most profound teaching. At times Jesus built his teaching directly around Proverbs – as we find in Luke 14:7–11 where, at the dinner in the Pharisee’s house, he reminded those present of Proverbs 25:6–7 which shows it is better to take the lower places of honor, and then to be invited to the head of the table. We even find important examples of Jesus’ use of Proverbs in one of the most spiritual of his teachings – the Sermon on the Mount. The Proverbs on the Mount In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus quotes from or alludes to Proverbs numerous times. For example, we can see the reflection of the proverb “… those who seek me find me” (Proverbs 8:17) in his words “seek and you will find” and “…the one who seeks finds” (Matthew 7:7–8). But the connections are more than incidental. When we look at many of the Beatitudes themselves, we find a remarkable inverse similarity to what Proverbs 6 tells us about the seven things God hates: This comparison does not include the final, 8th, beatitude “Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness …” (vs. 10) because only the first seven beatitudes, like the seven evils mentioned in Proverbs 6, are actual characteristics of the person. And although the Beatitudes cover many of the same ideas found in Proverbs 6:16-19 in a positive manner, we should remember that it was often typical of Jesus’ teaching to recast “negatively” worded concepts in a positive manner (Matthew 22:35–40, etc.). We should also not forget that Jesus compared himself to Solomon and stressed that his own God-given wisdom was greater than that of the ancient king (Matthew 12:42).

Wisdom certainly figures frequently in Jesus’ mountainside sermon, and he ends it by telling his hearers that: “… everyone who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice is like a wise man …” (Matthew 7:24). In the minds of Jesus’ listeners, such a “wise man” would have been no different from the individual held up as an example of right and godly living throughout the Book of Proverbs. This comparison is not to lower the Sermon on the Mount to the level of “human wisdom” or to elevate Proverbs to the level of Jesus’ highest teaching. It simply stresses that Proverbs contains ideas that were clearly part of the scriptural background and thinking of Jesus – ideas that are certainly worthy of our attention and that are often deeper than we may realize. * For much more information on the book of Proverbs, download our free e-book – Spotlight on the Proverbs – here. Seven Promises from the Words of Jesus

By R. Herbert. Living Belief Books, 2024, ISBN 979-8-89443-909-9 The promises recorded in the Bible are among the most important words in the Scriptures – and there are literally thousands of them! Even when we look only at the promises made by Jesus during his earthly ministry, there are hundreds of promises that could be considered. Yet many of these promises are prophecies that apply, for example, only to those who reject God, while others are clear promises made to those who submit their lives to him. That type of promise is of particular importance to every believer, and it is on those promises that this new book focuses. There are actually only seven such unconditional and ongoing promises that Jesus made regarding his relationship with his followers – promises for believers in every age – and it is these seven vital promises that this book examines. You can download a free copy of this new e-book to read on your computer, tablet, e-book reader, or smart phone, without registration or having to give an email address. Download a copy here. “[Jesus] went and lived in a town called Nazareth. So was fulfilled what was said through the prophets, that he would be called a Nazarene” (Matthew 2:23).

Skeptics and other critics of the Bible have long claimed that this verse shows Matthew was in error, as there is no verse anywhere in the Old Testament that matches this statement. It is true that there is no verse in our English Bibles saying exactly what Matthew wrote – but that does not mean that he was mistaken, or that his account of the life of Jesus was not inspired. First, we should notice that Matthew says “what was spoken” so it is certainly possible that he was aware of orally transmitted accounts of what certain prophets had said verbally, but there is another and perhaps more likely explanation for what he wrote. Second, there were no quotation marks in ancient Greek so Matthew may simply have paraphrased what some of the prophets had written. This becomes very likely when we realize that a number of verses found in the Old Testament speak of the messianic “Branch” who was foretold to come from the line of David. For example, the prophet Jeremiah wrote: “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the LORD, “When I will raise up for David a righteous Branch; And He will reign as king (Jeremiah 23:5 and see also 33:15). In Hebrew, the word “Branch” is netser and it is from this word that the name of the city of Nazareth is derived. We also find multiple references to the promised Messiah in the book of Isaiah – especially Isaiah 11:1 which tells us: “A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse; from his roots a Branch will bear fruit” (see also Isaiah 53:1; etc.). This is important because Matthew quotes Isaiah directly in Matthew 1:23 (Isaiah 7:14) and 4:12–16 (Isaiah 9:1–2), and these quotations from Isaiah’s messianic predictions make it very likely that the Gospel writer could have had Isaiah 11:1 in mind when he wrote Matthew 2:23. Matthew also says that the Messiah’s connection with Nazareth was confirmed by the “prophets” in the plural and, as we have seen, such a prophecy of the divine netser is found in both Jeremiah and Isaiah. Finally, we should remember that Matthew 2:23 is by no means unique in the Bible. The New Testament writers often did not have physical access to the texts of the Old Testament and many of their quotations from the Hebrew Scriptures are paraphrased slightly as they give a remembered meaning rather than a direct quotation. This principle is even seen in the Old Testament itself. The book of Ezra, for example, tells us “Your servants the prophets warned us when they said, ‘The land you are entering to possess is totally defiled by the detestable practices of the people living there. From one end to the other, the land is filled with corruption. Don’t let your daughters marry their sons! Don’t take their daughters as wives for your sons. Don’t ever promote the peace and prosperity of those nations. If you follow these instructions, you will be strong and will enjoy the good things the land produces, and you will leave this prosperity to your children forever” (Ezra 9:11–12 NLT). These exact words are not found in the Hebrew prophets, but the principles mentioned are found many times (Deuteronomy 7:1–4; etc.) and are clearly paraphrased in Ezra’s words. So, the fact that the exact words of Matthew cannot be found in the prophetic writings as we read them in our English Bibles does not mean that Matthew was mistaken, or have any relevance to whether his Gospel was inspired. The biblical writers often paraphrased each other, and summarized what other inspired writers had written before them. We can be assured that – as in this case – there are plausible answers to every supposed difficulty or contradiction within the books of the Bible.* * For further information on this topic, download our free book Scriptures in Question: Answers to Apparent Biblical Contradictions here. FINDING HAPPINESS : God’s Surprising Purpose in Your Life

By R. Herbert Although happiness is something we all want, perhaps above all else in life, most people look for happiness in the wrong places, live in ways that destroy what happiness they could have, or find only shallow and short-lived joy in their lives. Few people turn to the Bible to answer the question of where we might find lasting happiness, and even established believers rarely focus on what the Bible might teach them about this important topic. Yet the Bible contains hundreds of verses that show us how important happiness is, where we can find it, and how we can develop it in our lives. This non-commercial and non-denominational book looks at what the Bible teaches on this subject that can help you find the happiness you were meant to enjoy. Download a free copy directly – without registration or email address – here.  Several years ago we published an article on prayer that is still as valuable today as it was then. It makes a point that may transform your understanding of this subject. Not all prayer is asking for something, but a great deal of it obviously is. When we ask, do we pray mainly for our own physical and spiritual needs and concerns? It is certainly acceptable to pray for these things – we have Christ’s encouragement to do so – but that is only part of the picture we find in the words of Jesus and in the New Testament as a whole. The New Testament actually gives us an insight into an important aspect of prayer that we might easily miss. See what that 80% principle is, here. THE CENTURIONS:

LESSONS FROM TEN NEW TESTAMENT MEN OF VALOR By R. Herbert. The New Testament records the interaction of ten Roman military men with Christ and the early Christians. These ten men are shown as men of honor and valor who all played some role in establishing and furthering the Christian faith. The Centurions looks at positive lessons we can learn from each of them because each soldier shows us something regarding character traits that are as important now as they were then – as vital and valuable to the Christian warrior today as they were to the centurions of ancient Rome. You can download a copy of this new e-book directly – without registration or email – here. By Philip Shields*

Almost nobody you might ask – “who really ultimately was responsible for killing Jesus?” – gets it completely right. If you think I’m going to say we all killed Christ by our sins – please read on, because the full answer is much, much deeper and more meaningful even than that. Many say the Jews did. Certainly they’re right. They did. Paul and others attest to that (1 Thessalonians 2:14-15). Many say the Romans did. They’re right too – for it was the Roman government that had him nailed to the cross and who thrust the spear into his side. Still others say that we ALL killed Jesus of Nazareth. Peter seems to say this to his sorrowful Pentecost audience (Acts 2:36-37), and later to a group in Acts 3:12-17, see especially verse 15. How did we ALL kill the Christ? By our sins, which required his atoning death. All these answers are correct, but there’s one more answer to who really killed the Christ. What was the Messiah? One answer is what John the Baptizer said: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). Later, the apostle Paul referred to Christ as “our Passover Lamb” (1 Cor. 5:7), so the Passover and days of Unleavened Bread of Exodus 12 pointed to the REAL Lamb – the Lamb of God. Who was responsible in Exodus 12 to select a lamb without blemish and to have a lamb ready on Passover and to kill that lamb for their family in that original Passover service? It was the FATHER of the household who presented and killed the selected lamb (Exodus 12:3). So when we read that Jesus was called “the Lamb of GOD,” what was John referring to? God the Father had pre-selected the Word, who became flesh and became the Son of God (John 1:14) to be his Lamb. In fact, Jesus was as good as already slain from before the foundation of the world (Revelation 13:8; 1 Peter 1:18-20). ALL the Passover lambs of Exodus 12 and afterwards, all pointed to the future fulfillment of Messiah, the Lamb of God. God the Father presented a lamb for his household just as the Israelite fathers had to present one lamb or kid goat per household. (Exodus 12:3). The Lamb being offered had to be enough for the household. ALL who wish to be part of the Household of God will partake of Father’s lamb. So who really and ultimately had to kill the Lamb of God? Who alone truly could do it? Yeshua gave another clue during his final Passover, quoting from Zechariah 13:7. Then Jesus said to them, “All of you will be made to stumble because of Me this night, for it is written: ’I will strike the Shepherd, and the sheep of the flock will be scattered.’ (Matthew 26:31). Who is the “I” in “I will strike the Shepherd”? Who was going to strike the Shepherd? Remember that Christ was the Word who was God and WITH God (John 1:1-2). So let’s see what the original source – Zechariah13:7 – says, and notice how God calls that Shepherd “the Man who is my COMPANION.” it is God who is speaking. Jesus is quoted in Matthew 26:31 as saying “I will strike the Shepherd” – but he is quoting GOD speaking in Zechariah 13:7. So GOD will strike the Shepherd. Who is the Shepherd? Jesus himself says HE is the good shepherd (John 10:11); the Shepherd who would be struck by God. John 3:16 tells us that GOD so loved the world that HE gave his one and only Son so that those who believe in him would not perish but have everlasting life. God the Father saw that by sacrificing his only Son for a time he would be opening the door to potentially billions more sons and daughters (2 Corinthians 6:18). And Jesus was part of that plan from the beginning (John 10:17-18). Notice what Isaiah tells us about that: “Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; Yet we esteemed Him STRICKEN, SMITTEN BY GOD, and afflicted…. All we like sheep have gone astray, We have turned, every one, to his own way; And the Lord has laid on Him the iniquity of us all.” (Isaiah 53:4,6). Isaiah continues: “Yet it PLEASED the Lord to bruise him; HE has put him to grief. When YOU make His soul an offering for sin ... My righteous Servant shall justify many; For he shall bear their iniquities” (Isaiah 53:10-11). Did you catch that? HE – God – put his Servant-Son to grief. I know it’s easier to blame the Jews or the Romans, but that misses the point of the entire Passover lamb symbolism! Isaiah 53:10 says GOD made his Son’s soul an offering for sin in his love for all of us! Paul certainly understood this – that God “DID NOT SPARE HIS OWN SON, BUT DELIVERED HIM UP FOR US ALL” (Romans 8:32). So ultimately the One who killed Christ was the head of the Father’s house – God our Father. The blood of the Lamb of God, whom the FATHER slew for his household, protects us from the Destroyer, saves us from the penalty of death that we earned, and covers us by his grace. That is what the Scriptures say – that GOD gave his only begotten son as His LAMB for any and all who believe and who become a part of his household. * This post is condensed from the author's website (see https://tinyurl.com/348rbh8a) and is used here by kind permission. Sometimes a little biblical detective work can open new windows into our understanding of the stories of the New Testament.

The Priest The Gospel of John tells us that when Jesus was betrayed: “.… They bound him and brought him first to Annas, who was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the high priest that year” (John 18:12-13). The apostle John apparently knew some of the high priest’s family and was able to provide this detail not found in the other Gospels. Annas (also called Ananus and Ananias) himself was an interesting character. Serving as High Priest for ten years, from AD 6–15, this man was the patriarch of a dynasty of priests. Immensely powerful, when he was deposed by the Roman procurator Gratus, Annas maintained a high degree of power through arranging the appointment of his five sons (Eleazar, Jonathan, Theophilus, Matthias, Ananus) and his son-in-law, Caiaphas, to succeed him. The Jewish High Priest normally served for life (Numbers 35:25, 28), so the rapid-fire changes in succession after Annas suggest that he may have worked to ensure that he kept control of things as the real power behind the temple hierarchy. This maintaining power while technically deposed would explain why Annas was able to continue as head of the Jewish Sanhedrin (Acts 4:6) and perhaps explains why, when Jesus was arrested, he was first taken not to “Caiaphas, the high priest that year,” but to Annas. In fact, so real was Annas’ behind-the-scenes power that Luke records the word of God came to John the Baptist “during the high-priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas” (Luke 3:2). The Plot In his Gospel, the apostle John gives us another bit of information relative to the dealings of the chief priests. After Jesus raised Lazarus from the grave, John tells us that “a large crowd of Jews found out that Jesus was there and came, not only because of him but also to see Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. So the chief priests made plans to kill Lazarus as well, for on account of him many of the Jews were going over to Jesus and believing in him” (John 12:9). Again, John may have learned this perhaps because of his contacts in the high priestly households; but it is clear that this was a very real plot to get rid of not only Jesus himself, but also Lazarus as evidence of Christ’s miracle. Although Annas is not mentioned by name, it is inconceivable that such a plot would have been made without the knowledge of the chief priest and his sons – though it was more likely instigated by them as the “chief priests.” To understand the significance of this background, we must look at one of Jesus’ parables given at that time. The Parable In his parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, Jesus told his listeners: “There was a rich man who was dressed in purple and fine linen and lived in luxury every day. At his gate was laid a beggar named Lazarus …” (Luke 16:19-20). The parable continues to say that when he died, in the afterlife, the rich man implored the patriarch Abraham “… I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my family, for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment” (vss. 27-28). Notice that although the NIV says “to my family,” the Greek actually says “to my father's house” (as translated in the ESV and almost all other versions). When Abraham replies that “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them,” the rich man responds “No, father Abraham …but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent” (vss. 9-30). To this Abraham states conclusively: “… If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead” (vs. 31). The cast of characters in this parable are unmistakable. Although “Lazarus” is not specified to be the Lazarus of Bethany Christ raised from the dead, the New Testament does not speak of any other Lazarus; had it been a different individual, John would surely have identified him as he does in other instances when multiple people shared the same name. The “rich man who was dressed in purple and fine linen” is surely the high priest Caiaphas whose robes were exactly as described. Conclusively, the rich man has a father and five brothers. In the close families of ancient Palestine, “brothers” could mean blood bothers or brothers-in-law. So the identity of these individuals is clear – they are none other than Caiaphas (the rich man), Annas (the father) and his five sons (the brothers-in-law). If this were not the case, there would have been no reason for Jesus to include five brothers in the parable – the rich man could just have pleaded for his family. For Jesus’ original hearers it was doubtless clear that his parable made the point that just as the rich man’s father and brothers would not believe even after the return of the Lazarus of the parable from the dead, so the actual high priestly family had not believed when the real Lazarus had indeed been raised. Understood this way, the story of Lazarus and the rich man is paralleled by a number of other parables in which Jesus used actual historical situations of his day (see our free e-book on the parables for other examples). There is also perhaps a small practical lesson we can take from this understanding of Jesus’ parable: the unfailing discretion of Jesus. Although the characters of his parable may have been recognizable to his audience, Jesus did not go as far as identifying them by name. This fits the pattern we see throughout the New Testament in which Jesus never identifies and condemns individuals by name, only as groups – the Pharisees, scribes, tax collectors, or whatever. Although he could have publicly accused and discredited specific individuals on many occasions, Christ did not do so in his human life. In our own time – a time of heightened political invective – this is an example for every Christian to consider. * Download a free copy of our e-book Lessons from the Life of Jesus here. A BRIGHTER LIGHT:

SEVEN SIMPLE STEPS TO HELP YOUR CHRISTIAN LIGHT SHINE By R. Herbert Letting our “light” shine is a basic Christian responsibility, and this short book examines seven simple ways in which we can avoid short-circuiting the light God desires to show through us, and more effectively let that light shine. These principles can help us better reflect God’s nature, better do his work, and better fulfill his desire in our lives. Download a free copy of this new book directly – without registration or email address – from our sister site, here. When we read the Bible, we find the word “Christ” was originally a title (“the Messiah”) so the name "Jesus Christ" actually means, of course, “Jesus the Messiah. But in the New Testament the name is found as both “Jesus Christ” and “Christ Jesus” – is there a difference?

Because the New Testament was written by different authors over a number of years, it is perfectly possible that different authors might have had different preferences in expression. And a particular writer might vary in word choice for the sake of style, so a difference might not be one of meaning but simply of form. But it is also true that word order works a little differently in the Greek language than it does in English. In Greek there is flexibility in the order of words in a sentence that we do not see in the English language, with the variation in word order being a way to show emphasis. This has led to some commentators stating that “Jesus Christ” probably stresses the human side of the Son of God while “Christ Jesus” emphasizes his divine nature. Although this is a popular view, it is probably wrong. While “Jesus Christ” is found throughout the New Testament, we do not find the name “Christ Jesus” in the letters of Peter, John, James, or Hebrews. Most references to Christ Jesus are found in the writings of Paul (the only exception is in Acts 24:24, which discusses how Paul was talking to the Roman authority Felix about Jesus, so even there it is in a context related to Paul and influenced by him. So “Christ Jesus” seems to be primarily a Pauline expression, but what, if anything, did Paul mean by using it in distinction to “Jesus Christ”? For example, in the book of Philippians, “Christ Jesus” appears in Philippians 1:1, 8; and 2:5; while “Jesus Christ” is the form Paul uses in Philippians 1:2, 6, 11, 19; 2:11, 19. In the same way, in chapter 3 he speaks of Christ Jesus (3:3, 8, 12, 14), while he also refers to “Jesus Christ” (3:20). In Philippians 4, 4:7, 20, and 21 all have Christ Jesus, while 4:23 uses Jesus Christ again. Is there a pattern visible in the usage in these and other letters of Paul? Some commentators say that when Christ comes before Jesus, Jesus’ position as Messiah is emphasized by Paul while when Jesus is before Christ, his work as Savior is emphasized. This would not seem to be the case because Christ Jesus appears in places where his saving work is specifically emphasized (e.g., 1 Timothy 1:15: “The saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost”). I feel that there is a more likely reason for Paul’s usage of the two forms of Christ’s name. Paul will often use Christ Jesus in talking about how he is a servant or apostle of Christ Jesus, or when he stresses that we are “in Christ Jesus.” In other words, Paul seems to use “Christ Jesus” when he stresses a relationship with Christ – stressing Christ’s supremacy in the relationship. Paul does not deny Christ’s supremacy when he uses the more usual New Testament expression Jesus Christ, of course, but he seems to emphasize it when he uses the form “Christ Jesus.” Many people who read the book of Ruth think of it as a simple love story, but in reality it is far from simple, and it is not really a “love story” in the modern sense of romantic love, either. Nevertheless, the book of Ruth is a richly meaningful biblical story that can repay a little background study a great deal.

The first thing we should realize is that the central character of the book of Ruth is not really Ruth herself, but her mother-in-law, Naomi. In reality, the book of Ruth tells us far more about Naomi than it does about Ruth. The book begins and ends with Naomi, and when we look carefully we find that the narrative revolves around Naomi throughout most of the story – every event leads back to her. We can see how central Naomi is to the story when we realize that of the words spoken by all the characters in the book, 120 words are spoken by Ruth, while 225 – almost twice as many – are spoken by Naomi. It might be hard to find another story in which the supposed heroine speaks half as much as one of the supporting characters! People as Parables? For some, the story holds allegorical meanings with Ruth representing humanity, Boaz representing Christ, and Naomi the Christian Church that brings the two together. While this kind of symbolic interpretation of the book may seem attractive, almost endless variations exist regarding the symbolism that is supposedly involved. For some, Naomi represents the old covenant and Ruth the new covenant; others see yet different meanings. When we consider all the possibilities, we realize it would be difficult to discern which, if any, allegory might properly explain the book. It is true that the New Testament finds allegorical parables in many of the events recorded in the Old Testament. The parallels that can be seen between Christ and Abraham, Melchizedek, Moses, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, and other individuals are clearly spelled out in the New Testament, but that does not mean that every Old Testament story must fit this mold. In the case of the book of Ruth, we should remember that Ruth is only mentioned once in passing in the New Testament – in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:5) – and the story of Ruth is never alluded to, so we should be careful before we make comparisons that the Scriptures do not. Foreshadowing and Fulfillment On the other hand, when we look closely at the book of Ruth, it does contain an underlying theme – within the story itself – that undeniably foreshadows the gospel. At the beginning of the story, Naomi first loses physical sustenance in the time of famine and then loses her husband and sons. But when she hears that the Lord has restored food (literally “bread”) to Israel (Ruth 1:6), she leaves the region of Moab to travel back to Bethlehem (meaning “house of bread” or “house of food”) in the region of Judah called Ephrathah (meaning “fruitfulness”). Naomi's words to her daughters-in-law at that time reflect her emptiness. She tells them, “Do I still have sons in my womb that they may become your husbands?” (Ruth 1:11). Having lost her original home, her husband, and her sons, Naomi is figuratively empty. When she arrives in Bethlehem, she summarizes this emptiness when she says: “I went away full, but the Lord has brought me back empty” (Ruth 1:21). But in Bethlehem the narrative turns to describing the change from emptiness to fullness – both physically and figuratively. We are told that “the barley harvest was just beginning” (Ruth 1:22) and that Ruth goes to the fields to pick up the leftover grain at Naomi’s request (Ruth 2:2). As the story progresses, we see Ruth moving from simply gleaning in the poorest parts of the field to receiving more and more in the better areas from the hand of Boaz (Ruth 2:14-18). This “filling” of Naomi with physical bread precedes the figurative filling that occurs with the redemption of her property and the birth of “her” new son who comes as a result of the marriage of Ruth and Boaz. The “filling of the empty” through God’s grace underlies the whole book – which begins with stress on emptiness and concludes with stress on the fulfillment of good things. When we see the centrality of this message in the story of Ruth, we realize the importance of the list of names that concludes the book. Humanly, it is easy to see it as just an appendix that functions like the credits at the end of a film. We see it, but not as part of the story itself. Some even suggest this closing genealogy may have been added later; but if the book was composed by Samuel, as many scholars believe, there is no reason the genealogy could not date to that time. In any case, the genealogy forms the ending of the book as it was accepted into the canon of Scripture, and the genealogy leads, of course, to David – the king who became the ancestor of Jesus Christ. The Bread of Life In that sense, the book of Ruth foreshadows a double fulfillment – found first in David and then in his descendant, Jesus. This is because David was a messianic (“anointed”) king in ancient Israel (2 Samuel 23:1), but he also foreshadowed a much greater Messiah (Isaiah 9:1-7). The parallels between the messianic David, mentioned at the end of Ruth, and the later messianic figure of Jesus Christ are many and obvious. Both David and Jesus were born in Bethlehem, the city of bread which is the setting of most of Ruth. Just as David was prophesied to become king from Bethlehem (1 Samuel 16:1), so was the greater King who descended from him (Micah 5:2). David, the Bethlehemite king who provided bread for his people (2 Samuel 6:19, 1 Chronicles 16:3) foreshadowed the One who was himself the “bread of life” (John 6:35) and who would provide that spiritual bread for the salvation of his people (Mark 14:22). Perhaps we can see a reference to this ultimate fulfillment described in Ruth in the words of Mary, the mother of Jesus, at the annunciation of his conception – when she exclaims that God fills “the hungry with good things” (Luke 1:53). This is, in fact, a perfect summary of the message of the book of Ruth and what it foreshadows – a message about the God who not only provides physical bread for those who walk with Him, but who also provides, through Ruth’s eventual descendant, the bread of salvation. In fact, we meet the God who provides for His people – both physically and spiritually– as clearly in the book of Ruth as in any place in Scripture. *For more on the book of Ruth, download our free e-book Ruth: A Story of Strength, Loyalty, and Kindness here.  The Bible speaks about both the “gifts” and “fruit” of the Holy Spirit. Are these the same things? And if not, what is the difference – and should we be striving to develop one more than the other? There can be some overlap between what the Bible says regarding gifts and fruit of the Holy Spirit – both ultimately come to us through the Spirit of God – but there are also differences between the two. At the most basic level, gifts of the Spirit are given to us; fruit of the Spirit is developed in us over time – it is the result of the Spirit working in our lives. Put another way, God gives gifts, but he grows fruit in our lives. It is important that we understand other differences, also. Gifts of the Spirit The Scriptures speak of a number of gifts of the Spirit of God (1 Corinthians 12:4). For example, Romans 12:6-8 lists the gifts of prophesy, serving, teaching, encouragement, giving, leading, and showing mercy. 1 Corinthians 12:8-10, on the other hand, mentions wisdom, knowledge, faith, healing, miraculous powers, prophecy, discernment of spirits, speaking in different languages, and the interpretation of languages. As you can see, apart from the mention of prophecy, these two lists are quite different. So we have to put many scriptures together to find all the gifts the Bible enumerates, and even the combined lists are doubtless not complete regarding all the possible gifts God can give. Overall, however, it is clear that the gifts of the Spirit are outward flowing to accomplish the work of God. They often represent skills or aptitudes that we are given in order to better serve. As such, no one receives all the gifts of the Spirit, and no single gift is given to all God’s people (1 Corinthians 12:28-29). But every Christian is given at least one gift either at conversion (Ephesians 3:7-8) or as the need arises. Each one of us is given the gift of an aptitude or skill, and it is our responsibility to identify that gift and to put it to work to help others (1 Peter 4:10). Some gifts may seem more impressive than others, but every gift is important and necessary in the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:21-23). But just because these gifts are given through the Spirit of God does not mean we have no part in developing and using them. Take the gift of knowledge, for example. God does not simply pour facts into our minds. He blesses us with an aptitude for learning and understanding things and perhaps also in being able to memorize facts and to see their significance. In any case, we must work in order to use the gifts we are given. And we must always remember that unless we use our gifts and use them in love and not for self-aggrandizement, they are rendered useless (1 Timothy 4:14, 1 Corinthians 13:1). Fruit of the Spirit When we turn to the Bible’s words on the fruit of the Spirit we find very different things. The fullest list is in Paul’s letter to the Galatians, where we find: “love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control…” (Galatians 5:22-23). These qualities are clearly different from those the Bible calls the gifts of the Spirit. Although they all have outward manifestations, they are attributes that signify inner changes in our very nature. For example, we can increase in the gift of knowledge, yet our behavior may not change; but we cannot truly increase in the fruit of love or patience without our behavior being affected. In fact, the fruit listed in Galatians 5:22-23 is in direct contrast to the acts of carnal human nature listed in the preceding verses in Galatians 5:19-21. Although Paul mentions nine specific qualities, he speaks of the singular “fruit” of the Spirit rather than the plural “fruits” – indicating that the various qualities are perhaps all aspects of the central quality of love. But whether this is the case or not, we need to develop as many of the aspects as possible in order to produce spiritual fruit in every part of our lives: “so that you may live a life worthy of the Lord and please him in every way: bearing fruit in every good work, growing in the knowledge of God” (Colossians 1:10). While we are individually limited to which gifts of the Spirit we receive, we can develop all of the fruit of the Spirit and we should strive to develop it all as much as possible. Jesus himself referred to this in saying “This is to my Father’s glory, that you bear much fruit, showing yourselves to be my disciples” (John 15:8). So we can summarize by saying that the gifts of the Spirit primarily involve what we do, while the fruit of the Spirit involves what we are. There is certainly overlap in some areas – gifts can appear to change us inwardly and fruit is manifested in our outward behavior. But the differences teach us important lessons. We must not neglect to nurture and develop fruit in our lives just because it is clear that we have been given gifts and we are busy utilizing them. In the same way it is imperative that we do not concentrate entirely on developing fruits in our own lives while neglecting to use the gifts we may have been given to serve others. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul says that we should “earnestly desire the best gifts…” (1 Corinthians 12:31), yet he also stresses that the gifts are nothing without the fruit underlying them (1 Corinthians 13). Jesus also reminds us (John 13:35) that men would recognize us as his disciples not by our gifts – but by our fruit. Each of the four gospels contains information on the life of Jesus that the others do not. But almost half of what we read in the Gospel of Luke is not found in any of the other three gospels. If it were not for Luke, we would not have much that we know about the life of Jesus, or many of his most famous teachings – such as the parables of the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, and many others. Luke contains so much unique material that it is worth especially careful study – and this e-book opens up the third gospel in unique ways to show you just how much you have been missing! Download your free copy here.

In his second letter to the Corinthians, the apostle Paul wrote of the revelations that had been given to him, then tells us “in order to keep me from becoming conceited, I was given a thorn in my flesh, a messenger of Satan, to torment me. Three times I pleaded with the Lord to take it away from me. But he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness’” (2 Corinthians 12:7-9).

The identity of the “thorn” in Paul’s flesh has often been debated, and there are several possibilities regarding its nature. The most commonly accepted interpretation is that the thorn Paul suffered was some kind of physical weakness or “infirmity.” Supporters of this view often point out that Paul mentions the large letters he used in writing to the Galatians (Galatians 6:11), and he also mentions that the Galatians would have plucked out their own eyes and given them to him (Galatians 4:13-15) – both of which might indicate an ongoing physical eye problem. But Paul also says in verse 13 of Galatians 4 that his weakness was “at first” – which gives the impression that it was a temporary thing from which he recovered (very possibly the stoning Paul suffered in Galatia that he describes in the same chapter ). Additionally, weakness or infirmity need not mean a physical ailment in 2 Corinthians 12:9–10. In 2 Corinthians 11:30, Paul uses the same terminology of “glorying in weakness” that he uses a few verses later in speaking about the thorn he was given. In fact, in the earlier chapter Paul lists a number of “weaknesses” he had suffered – such as imprisonment, whippings, shipwrecks, and stonings – but does not mention any specific physical ailment (2 Corinthians 11:23–29). So, many scholars prefer to look for another explanation of Paul’s thorn in the flesh. All of the things listed in 2 Corinthians 11 as weaknesses or infirmities are forms of persecution and, in context, Paul’s thorn could have been ongoing persecution that was stirred up against him and which prevented him from fully doing the work he wished to do. In fact, the description of persecution as a “thorn” is found several times in the Old Testament. In Numbers 33:55; Joshua 23:13; and Judges 2:3, enemies of Israel are spoken of as being “thorns in your sides” and “thorns in your eyes.” In Paul’s case, the apostle elsewhere mentioned Alexander the coppersmith (2 Timothy 4:14), Hymenaeus, and Philetus (2 Timothy 2:17), and others as persecuting him and hindering his work, so he may have had people like them in mind as being “thorns” to him and adversaries of the gospel. Understood this way, Paul asked God to remove ongoing persecution from him, not sickness, and was told that God’s grace or help is with us in those situations – that we are sometimes not redeemed from persecution, just as Paul himself stated when he later wrote, “everyone who wants to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted” (2 Timothy 3:12). But the Bible does not precisely identify Paul’s thorn in the flesh. Many commentators simply gloss over this fact by saying the nature of Paul’s thorn does not matter or God would have recorded it so we would know what it was. But there is a far simpler and more likely understanding of Paul’s failure to identify what troubled him. Paul may have been intentionally vague because God inspired him not to directly identify his thorn so that people with various physical and spiritual problems could identify with Paul and understand his point in mentioning his suffering – that we can all experience the same grace that Paul did, because Christ’s power “is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9) – whatever our weakness or infirmity might be. “Those who had arrested Jesus took him to Caiaphas the high priest … But Peter followed him at a distance, right up to the courtyard of the high priest. He entered and sat down with the guards to see the outcome” (Matthew 26:57-59).

The description of Peter – who had only recently insisted that he would follow Jesus to the death if necessary (John 13:37) – as following at a safe distance after Jesus’ arrest is one of the most unflattering stories in the New Testament. When the “chips were down,” Peter did not stick with the One he acknowledged as the Christ; though later, after his empowerment by the Spirit of God, he did, of course, follow Jesus to the end. There are two aspects of what Matthew says about this event that we can apply to ourselves – two ways that we too can fail in following. First, we see that Peter “followed him at a distance.” Do we do this in our lives? If we are only partially involved in our religious beliefs, if we think of our religion as only what we do in church, and not in our everyday lives, we are certainly following Him at a distance. But there is also another type of distance following. We can fail to follow closely in time as well as in space. Notice that when Peter followed Jesus to the high priest’s courtyard he then “sat down ..to see the outcome.” Do we wait to see the outcome of things before committing ourselves to following more closely? That is the attitude of millions of people through history who have attempted to strike a bargain with God: “If you will do this – rescue me, heal me, help me or whatever – I will do better, follow you more closely.” Although God may sometimes intervene to answer sincere prayers of this type, we must beware of putting off obedience until God has “done His side of the deal.” We can do this, for example, by waiting till we feel our finances are in order before helping others, or in countless other ways. Although we may feel we are sincere in these things, it’s really just following at a safe distance. We need to be following in the here and now. It helps to remember that “Follow me” was Jesus’ first command to his disciples (Mark 1:17), and it is also his last recorded command in the Gospel of John (John 21:19). Significantly, it was to Peter that Jesus addressed that command, and repeated it, after his resurrection (John 21:21), though it clearly applies to every disciple. Peter had to learn, and be reminded, that following Jesus and saying we are following Jesus are not the same – and that following at a distance is not really following at all. It’s a lesson we all need to remember at times, because God wants real followers rather than those of the “distant” or “eventual” type. We see this in the Old Testament where God says: “Because they have not followed me wholeheartedly, not one of those who were twenty years old or more when they came up out of Egypt will see the land I promised …” (Numbers 32:11). We see it throughout the New Testament where numerous people failed to follow because they wanted to follow later, or at a distance: “[Jesus] said to another man, ‘Follow me.’ But he replied, ‘Lord, first let me go and bury my father’ …. Still another said, ‘I will follow you, Lord; but first let me go back and say goodbye to my family’ ” (Luke 9:59-61). The whole point of following is really to follow as closely as possible. Jesus was explicit about this, saying: “Whoever serves me must follow me; and where I am, my servant also will be” (John 12:26). That clearly implies following by walking with him rather than following at a safe distance. * * * You may like the latest blog post on our Tactical Christianity website here. Every Christian knows that Jesus Christ was born in Bethlehem, but many do not know why. There are actually two reasons why Jesus was born in that tiny Judean village, and both can be found in Scripture. First, it was foretold that the Messiah was to come from the house of David – to be a descendant of the young shepherd who became king of ancient Israel 1,000 years before the time of Christ. This was promised to David himself:

“When your days are over and you rest with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, your own flesh and blood, and I will establish his kingdom … and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be his father, and he will be my son … Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever” (2 Samuel 7:12-16). This prophecy could not have been completely fulfilled by David’s physical descendants, but only by a Messianic King who could rule “forever” (vss. 13, 16). That is why in the New Testament it was foretold of Jesus: “He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David” (Luke 1:32), and why, of course, Jesus is called the “Son of David” throughout the Gospels. So the Davidic sonship of the Messiah was one reason for his eventual birth in Bethlehem – the place where David was born (and crowned) and his ancestral home (1 Samuel 17:12). As a descendant of David, Joseph, the husband of Jesus’ mother Mary, was required to travel to Bethlehem for a Roman census: “In those days Caesar Augustus issued a decree that a census should be taken of the entire Roman world. (This was the first census that took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria.) And everyone went to their own town to register. So Joseph also went up from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to Bethlehem the town of David, because he belonged to the house and line of David” (Luke 2:1-4). But there is another reason for the Bethlehem nativity. The Old Testament Book of Micah contains a fascinating prophecy of what was to occur in the fulfillment of God’s promise of the Messiah: “And you, O tower of the flock, hill of the daughter of Zion, to you shall it come, the former dominion shall come, kingship for the daughter of Jerusalem … But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah, who are too little to be among the clans of Judah, from you shall come forth for me one who is to be ruler in Israel, whose coming forth is from of old, from ancient days. … And he shall stand and shepherd his flock in the strength of the Lord, in the majesty of the name of the Lord his God. And they shall dwell secure, for now he shall be great to the ends of the earth. And he shall be their peace” (Micah 4:8, 5:2-5). This prophecy tells us that the Messianic ruler who would shepherd his people was, like David, to come from Bethlehem and that he would eventually reign “to the ends of the earth.” But notice another detail. The prophecy begins “And you, O tower of the flock …” for which the Hebrew is migdal eder, literally “Tower of Eder.” This tower is first mentioned in the Book of Genesis. It stood on the outskirts of Bethlehem where the patriarch Jacob’s wife Rachel (Genesis 35:18-19) gave birth to her son “Ben-Oni” (meaning “son of sorrow”), whose name was changed to Benjamin (“son of the right hand”). In New Testament times, the tower was a watchtower used to guard the flocks of sheep that were pastured in that area. The Jewish Mishnah (Shekalim vii. 4) indicates that sheep in the fields around Migdal Eder were controlled by the Temple in Jerusalem and were used to provide the animals sacrificed in the temple rituals. A number of biblical scholars have pointed out that if the prophecy of Micah 4:8 was fulfilled literally, then Jesus may well have been born in some building in this general part of the outskirts of Bethlehem. The word translated “manger” where the infant Jesus was placed (Luke 3:7) could also be translated as “stall” or any holding area for animals. More importantly, have you ever wondered why the Gospel of Luke tells us that at the Nativity, angels appeared to shepherds? The heavenly host could have appeared, of course, to a group of soldiers, priests, travelers, or any other individuals, but we are told that they appeared to shepherds who were grazing their flocks in the area where Jesus was born (Luke 2:8-15). If Jesus was born in the area of Migdol Eder, the area where the sacrificial lambs were born and raised, the shepherds would naturally have been the people present in that area. But regardless of the details of its fulfillment, the intent of the prophecy of Micah is clear. The promised Messiah who was the Lamb who would be sacrificed for his people (John 1:29) would also be their future Shepherd (Matthew 2:6). We see this principle throughout the Gospels, which speak of Jesus in both his initial human and later divine roles – as both the Servant and the future promised King, the Captive and the future Warrior, the Judged and the future Judge (Matthew 25:32, etc.). In every case, at his first coming Jesus fulfilled the lesser role, and at his second coming he will fulfill the greater role. And there is a lesson in this for us. As we read the Gospel accounts and reflect on the life of Jesus, we should look carefully at how he carried out the lesser roles he fulfilled as a human being. These roles are recorded so that our present lives may be modelled on his – just as he promises to eventually share his greater roles with us if we are faithful in the lesser ones we have now (Luke 16:10). ----- * You may like the latest blog post on our Tactical Christianity website here. The expression “in the Name of Jesus” or “in Jesus' Name” appears many times in the New Testament and most Bible readers realize that it means something is being done with the authority of Jesus or “on Jesus’ behalf.” We see this meaning of “by his authority” in what Jesus himself told his disciples: “Until now you have not asked for anything in my name. Ask and you will receive, and your joy will be complete” (John 16:24).

Many Christians use the words “in Jesus’ name” frequently and only with this meaning, almost like a magical formula or written guarantee of answered prayer; but this is not what Jesus intended, as many scriptures show (2 Corinthians 12:8–9; etc.). It is also important to realize that the expression “in Jesus’ name” can also have a number of other, quite different meanings in the New Testament. In fact, “by Jesus’ authority” is only one of seven meanings of “in Jesus’ name.” Consider the following six other meanings: Proclaiming the Gospel. In the book of Acts we read that the Jewish leaders commanded the disciples using “in the name of Jesus,” but certainly not by his authority. “Then they called them in again and commanded them not to speak or teach at all in the name of Jesus” (Acts 4:18). This does not mean “by Jesus’ authority,” as the unbelieving Jews did not acknowledge that he had any – they meant the disciples should not teach what Jesus taught (see also Acts 5:40). Speaking or acting with the character of Jesus. In biblical culture, a person’s name was often related to the character of the individual. In this sense, to say or do something in Jesus’ name is to bring the nature of Jesus’ character to bear on the issue – as when Paul wrote “In your lives you must think and act like Christ Jesus” (Philippians 2:5 NCV). This means we do whatever we do not by Jesus’ authority, but as he would do it. Doing something as if for Jesus. There are verses where “in Jesus name” means doing something as if for Christ – as when Paul wrote: “And whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus” (Colossians 3:17). We do not do our jobs or mow our lawns “by authority of Jesus” – in this sense the expression clearly means we do things as though for Christ. Earlier in the same epistle Paul tells us “Work willingly at whatever you do, as though you were working for the Lord rather than for people” (Colossians 3:23 NLT). Giving thanks through Jesus. Paul shows this meaning of “in the name of Jesus” when he wrote that we should be “always giving thanks to God the Father for everything, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Ephesians 5:20). As our intermediary, Jesus conveys our thanks to the Father – in his name – and we are “giving thanks to God the Father through him” (Colossians 3:17). Aligning our will with that of God. Doing something “in the name of Jesus” can sometimes mean we align our will and our petitions with his. This can be seen when Jesus said “I will do whatever you ask in my name, so that the Father may be glorified in the Son. You may ask me for anything in my name, and I will do it” (John 14:13–14). This does not mean that whatever we pray for will be granted if we just ask in Jesus’ name, but that when we pray things to glorify the father – that are in line with his will – they will be granted. This is not about Jesus’ authority, but his way of always praying according to the Father’s will. Into the name or body of Jesus. The Greek preposition eis translated as “in” in the phrase “in the name of Jesus” can also mean “into,” and this appears to be the meaning of a number of the verses in the book of Acts that speak of people being baptized in Jesus’ name. We read, for example: “On hearing this, they were baptized into the name of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 19:5 ASB, BSB, CSB, etc.). In this and similar verses the stress is on being baptized into the body of Christ: “For in one Spirit we were all baptized into one body” (1 Corinthians 12:13 ESV, etc.). So there are at least seven different meanings to the expression “in the name of Jesus” in the New Testament, and we must look carefully at the context where each occurs in order to see its specific meaning. The name of Jesus is the name above all names (Philippians 2:9–11), but it is not a magical formula given for our personal use (Acts 19:13). On the other hand, “in Jesus’ name” has rich and varied meanings that well repay our study and thought. ----- *You may like the latest blog post on our Tactical Christianity website here. “Then Jesus said to them, “Suppose you have a friend, and you go to him at midnight and say, ‘Friend, lend me three loaves of bread; a friend of mine on a journey has come to me, and I have no food to offer him.’ And suppose the one inside answers, ‘Don’t bother me. The door is already locked, and my children and I are in bed. I can’t get up and give you anything.’ I tell you, even though he will not get up and give you the bread because of friendship, yet because of your shameless audacity he will surely get up and give you as much as you need” (Luke 11:5-8).

The parable of the Friend in Need (or the Friend at Midnight) appears in the Gospel of Luke immediately after Jesus gives his disciples the “Lord’s Prayer” and is clearly a continuation of his teaching on how to pray. Three cultural aspects help explain the details of the parable. First, in the ancient Near East, ovens were fired and bread was usually baked in the early morning hours before the heat of the day – so by nightfall there might well be no bread left in a home, and people would borrow from their neighbors if more was needed. Second, and also because of the heat of the days, it was not unusual for people to wait till evening to set out on a journey and to arrive at their destination later in the night. Finally, Near Eastern custom was such that if someone arrived at one’s home after a long journey, it would be regarded as shameful not to offer the person food. This seems to be the situation in which the man in the parable finds himself, so he goes to his friend’s house late at night to request food for his guest. The obvious lesson in the parable is that of persistence in prayer, something Jesus taught on multiple occasions, and in other parables such as that of the Persistent Widow. But perhaps we may find other lessons in this particular parable as well. For one thing, we see in the action of the friend that he was doing everything he could do himself – going to a friend’s house, even late at night, and asking tirelessly until he received a positive answer. The Greek word which is translated “boldness” or “persistence” in some translations, regarding how the man continues to ask his friend’s help, is well translated as “shameless audacity” in the NIV – it really does convey an attitude that goes beyond simple persistence to a level which might even seem audacious or rude. This, Jesus tells us, is the kind of persistence we should have in prayer — a confident boldness we also see in the story of the woman of Syrophoenicia who persisted in asking Jesus’ help till he rewarded her for exactly this attitude (Mark 7:25-30, Matthew 15:21-28 and see also Hebrews 4:16). But we should also remember a final detail of this parable: that it is not based on the friend needing bread for himself, but for someone else. So an additional lesson we can draw from this story is that we can often be the answer to someone else’s need. That is what intercessory prayer is all about, and this small parable reminds us to pray for others not only tirelessly, but also with true boldness. * * * See also the latest blog post on our Tactical Christianity website here. When we think of the biblical concept of rest, we probably think first of the Sabbath rest (Exodus 20:8-11), or Jesus’ words to his disciples: “Come… apart … and rest a while” (Mark 6:31 ASV), but beyond this kind of resting by ceasing from activity, the Bible shows that our attitude also affects our ability to rest.

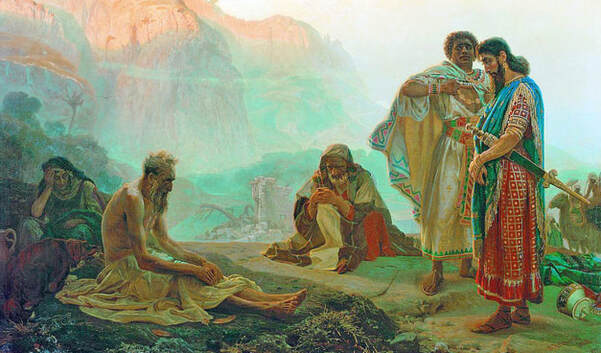

If we think about it, both the examples of rest given above involve humility – we have to be humble enough to accept God’s command to regularly rest, and we have to understand that we are not so important to the functioning of the world that we cannot step back and take additional rest when we need to do so. In fact, the Bible shows that full physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual rest is more than just the cessation of activity – we can stop work and still not find rest – and the Scriptures elaborate on this fact, showing there is a deep connection between rest and humility. This is most clearly seen in Jesus’ words: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls” (Matthew 11:28–29). Although this is a scripture most Christians know well, we rarely focus on the relationship between the deep, fulfilling rest Christ promises, and the humility he says it is based upon. Yet if we look at the Scriptures carefully, we see this principle repeated often. Sometimes we see it plainly in the grand sweep of biblical stories, just as Job only found rest and peace from his trials after finally being humbled. At other times we can see the principle in small details, as when King David wrote: “My heart is not proud, LORD, my eyes are not haughty; I do not concern myself with great matters or things too wonderful for me. But I have calmed and quieted myself” (Psalm 131:1–2). Hannah Anderson, author of the book Humble Roots (Moody, 2016), perfectly summarized the clear relationship between humility and rest this way: “[God] frees us from our burdens in the most unexpected way: He frees us by calling us to rely less on ourselves and more on Him. He frees us by calling us to humility.” And Anderson shows us why this is so: “Pride convinces us that we are stronger and more capable than we actually are. Pride convinces us that we must do and be more than we are able. And when we try, we find ourselves feeling, ‘thin, sort of stretched… like butter that has been scraped over too much bread.’ … We begin to fall apart physically, emotionally, and spiritually for the simple reason that we are not existing as we were meant to exist.” Sometimes circumstances prevent or delay proper rest, of course, but it is important that we do not continually live this way – and that we come to see rest not only as a divinely mandated responsibility, but also as a gift that we ignore to our own hurt. If we live out our days in a lifestyle that avoids or diminishes rest, always struggling to increase some metric of our lives or never quite letting go of our own thoughts and pursuits, sooner or later we begin to experience the problems Humble Roots describes. The truth is, despite our striving and whatever our occupation, our work will never be done, and one of the Christian’s most basic life lessons must be that we will never experience true rest as long as we focus on what we need to do and to accomplish, instead of learning to rely on God and not ourselves. The sin of pride has been well defined as simply overestimating ourselves and underestimating God; and it is only as we learn to humbly put our own lives and concerns aside in rest that we acknowledge God’s true nature and our own, and see things in proper perspective. The nineteenth-century clergyman and author, Phillips Brooks, once wrote: “The true way to be humble is not to stoop until you are smaller than yourself, but to stand at your real height against some higher nature that will show you what the real smallness of your greatness is.” Rest not only allows us to do that, but also it helps us to do that. Hebrews 4:9 tells us “There remains, then, a Sabbath-rest for the people of God” and although the rest indicated in this verse is primarily a future one, in the kingdom of God, the principle applies now also. We must remind ourselves that the will of God is not that we should work endlessly in this life and then enjoy rest later, but that we should experience the rest and peace in this life that reflects the rest and peace we will have in eternity. We humble ourselves by resting physically and spiritually, and – as Christ himself promised – as we learn humility, we find rest. There are many lessons to be learned from the book of Job, and among them are important lessons we can learn from his friends. Despite their lack of understanding regarding Job’s situation and the errors they made in what they said in that regard, Job’s friends got some things right and their story can teach us worthwhile lessons in helping those who are suffering:

1. They were attentive. Although Job and his friends were separated by considerable distances, they obviously stayed in touch to the extent that they knew that Job was suffering and could use their encouragement. We cannot help others if we fail to stay connected and are not attentive to their needs – whether they are friends, co-workers, aged family members, or others. Job’s friends were not so wrapped up in their own lives that they were disconnected from his; they were not too busy to stay in touch and see when he needed them. 2. They got involved. When they became aware of Job’s situation, his friends acted on the knowledge. They did not simply pray for Job – right and proper as that would be – they got involved to do what they could do directly. The friends doubtless sacrificed considerable time and energy in traveling to Job from other lands, and they apparently came at once rather than waiting for a convenient time, after the harvest, after the summer heat, or whatever. 3. They coordinated. Job 2:11 tells us that Job’s friends: “met together to go and sympathize with Job and comfort him,” or, as the ESV translates this verse: “They made an appointment together to come to show him sympathy and comfort him.” The three friends clearly coordinated with each other to help Job. We can learn from this by seeing the value of reaching out to let others know of a person’s need and by helping to coordinate visits or help for the individual from different people at different times. 4. They reacted appropriately. The Bible tells us to “Mourn with those who mourn” (Romans 12:15), and we are told that when Job’s friends saw him “they began to weep aloud, and they tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads” (Job 2:12). Tearing one’s clothes and throwing dust or ashes on oneself was a sign of mourning in the ancient world, and this is what Job himself had done (Job 2:8). Jobs’ friends grieved deeply for him and they expressed their emotions in clear but appropriate ways that helped Job see they identified with him and his suffering. 5. They did best when they said less. The friends said nothing for seven days (2:13), and while they commiserated in silence the friends did no wrong. It was only once they began to comment on the situation that their mistaken assumptions of Job’s guilt made him even more miserable and eventually earned a rebuke from God himself. The friends’ statements about children who do wrong or who suffer for their parents’ wrongdoing (Job 5:4; 8:4; 21:19; etc.) were doubtless especially painful to Job who had just lost his own children (Job 1:5). Often, when people are suffering, we may try to say something to make the situation better or to offer encouragement – but what we say at such times can inadvertently appear to be arguing with the sufferer or hurt in other ways (Job 16:4; 19:2). Job’s friends showed there are times when it is better to say less and allow our physical presence to do most of the talking. 6. They stayed with Job. Despite their failings with words, Job’s friends stayed with him for at least seven days – it was no quick visit just to offer condolences. We may not always be able to give up extended periods of time to help others, but the principle of staying with the sufferer means doing things such as continuing to contact them, to see if they need help and to give them an opportunity to talk about their situation. We should notice that even when the friends stopped trying to speak to Job (Job 32:1), they did not leave for home – they stayed and continued sitting with him for some time. These six lessons are simple enough, but applying them in our interaction with those who are suffering can make a great deal of difference. When we consider what the Bible clearly shows regarding God’s promised judgment on sin and unrepentant sinning humans, it is easy to see only the darker tones of the prophetic picture and to miss the highlights of goodness, mercy and compassion that are also there. Looking at the messages of the Old Testament prophets, for example, it is easy to miss seeing the loving God behind the looming punishments. Even in Isaiah – one of the most positive and uplifting of the prophetic books – it can often be hard to see the love in the graphic words of judgment aimed at Israel, Judah, and their surrounding nations. Yet the goodness of God is there, nonetheless.

While Isaiah 13–23 and other chapters consist of dire “burdens” or pronouncements on the nations, we must not overlook the attitude of both the prophet and the God who inspired him. After reading the promised violent destruction of Israel’s enemy, Moab, for example, we should not miss Isaiah’s words “My heart cries out over Moab” (Isaiah 15:5), and his statement “My heart laments for Moab like a harp, my inmost being for Kir Hareseth” (Isaiah 16:11) – showing the deep underlying divine sympathy even for those who must be punished in the extreme. But perhaps the clearest place in which God’s attitude toward those who must receive his punishment is found is in the Bible’s final book and final word of judgment – the book of Revelation. God’s judgment against sin and wrongdoing is repeatedly shown to be both final and fierce, leading many skeptics to claim that Revelation shows a “harsh” God – as they claim many of the prophetic books of the Old Testament also do. But Revelation shows that this is not the case. Just as the Old Testament acknowledges God’s righteousness in judgment – as when Abraham declares “Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?” (Genesis 18:25), and the Psalmist declares that “righteousness and justice” are the foundation of God’s throne (Psalm 89:14) – so the Greek word for righteousness used repeatedly throughout Revelation is dikaiosuné which carries the dual connotation of both righteousness and justice. Revelation asserts this justice is based on the righteousness of God: “You are just in these judgments, O Holy One …Yes, Lord God the Almighty, true and just are your judgments!” (Revelation 16:5, 7) and of Christ: “Then I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse! The one sitting on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war” (Rev. 19:11 ESV, emphases added here and below). Revelation shows that despite the patience God displays to the wicked, he will eventually judge and destroy evil – and this theme underlies chapters 6–20, the bulk of the book. In two passages within those chapters (Rev. 14:14–20 and 19:11–16) we are given graphic symbolic summaries of God’s judgment (one of several indications that several scenes in Revelation may be parallel views of the same event rather than sequential events), and it is not coincidental that both passages speak of God’s “wrath” (Rev. 14:19; 19:15). But this wrathful judgment is for a purpose – it is loving anger aimed at freeing humanity from sin rather than vengeful anger intended to simply punish God’s mortal children. To see this, we must look closely at the imagery used by Revelation. The punishments described in the central chapters of the book culminate in the catastrophic plagues poured out on humanity in chapters 15 and 16. The images used in this climactic part of Revelation closely resemble the plagues God brought on Egypt to enable the Exodus. That is why, as the plagues begin, a heavenly chorus is said to sing “the song of God’s servant Moses and of the Lamb” (Rev. 15:3). It is sometimes said that this song reflects God’s law (Moses) and grace (the Lamb), but this misses the point that Moses oversaw and administered the same kind of plagues on Egypt so that it would release Israel from slavery that the Lamb will administer on the powers that hold all humanity in sin, as well as those who will not submit to him. Notice how the song stresses the justness of this punishment: “Great and marvelous are your deeds, Lord God Almighty. Just and true are your ways, King of the nations. Who will not fear you, Lord, and bring glory to your name? For you alone are holy. All nations will come and worship before you, for your righteous acts have been revealed.” (Rev. 15:3–4) Truly, the final plague-punishments of Revelation conclude in a redemption that is far greater than that of Israel’s release from Egypt. Now, instead of only Israel coming to worship God (Exodus 8:1; etc.), all nations are said to turn to him– for the specific reason that God’s acts have been revealed and recognized as righteous judgment (Rev. 15:4). These are the very same nations that were said to rage against God in Rev. 11:18, but God’s righteous judgment does not destroy them – it frees them from sin and leads to their eventual salvation (Rev. 12:10). This point is nowhere more clearly made than in Revelation, but it is not a new theme in the Bible. The Psalmist wrote “Let all creation rejoice before the LORD, for he comes, he comes to judge the earth. He will judge the world in righteousness and the peoples in his faithfulness” (Psalm 96:13). God’s judgment and punishment have always been, and always will be, made in righteousness and love. We are all so used to hearing people say “Amen” at the end of prayers and saying it ourselves that we seldom think about the word, but the following points may show you that there is a lot about that small word you don’t know.

1) “Amen” doesn’t just mean “may it be so.” Many people think of amen as a kind of spiritual punctuation mark – something we put at the end of prayers to mean “the prayer is over.” Those who understand the word better think of it as meaning “may it be so” and being a way of adding our agreement to what was said, but the word means much more than that and actually has a number of meanings. Amen comes from a Hebrew root which in its various forms can mean: to support, to be loyal, to be certain or sure, and even to place faith in something. At the most basic level, the word can mean simply “yes!” as we see in Paul’s statement: “For no matter how many promises God has made, they are ‘Yes’ in Christ. And so through him the ‘Amen’ is spoken by us to the glory of God” (2 Corinthians 1:20). But the central meaning of the word has to do with truth, as we will see. 2) Amen was not usually used to conclude prayers in the Bible. Although it is found many times in the Bible, its main use was to affirm praise for God (Psalm 41:13; Romans 1:25; etc.) or to confirm a blessing (Romans 15:33; etc.) – either by the speaker or the hearers. The “amen” found at the end of the Lord’s Prayer in some manuscripts of the New Testament affirms the expression of praise that concludes the prayer. Perhaps because of this, over the course of the centuries it became common practice to use “amen” as the conclusion for prayers. 3) Amen is used as a characteristic of God in the Old Testament. Although the English Bible translation you use may not show it, in Isaiah 65:16 the Hebrew text speaks twice of “the God of Amen,” and this clearly uses amen as a characteristic or even a title of God. Because many translators feel this would be confusing in English, they choose to render the text as “the God of truth,” and although that is not a bad translation, it does somewhat obscure the original sense of what was written. 4) Amen is used as a characteristic of Jesus in the New Testament. Just as God is referred to as the God of Amen in the Old Testament, so in the New Testament in Revelation 3:14 “Amen” is used as a title for Jesus Christ “These are the words of the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the ruler of God’s creation.” The combination of Amen with “faithful and true witness” clearly show the connection between amen and truth. 5) Amen was used uniquely by Jesus. Jesus usually used the word amen at the beginning of his statements, and in those cases, it was sometimes translated by the Gospel writers into Greek as “truly” (Luke 4:25; 9:27; etc.). The NIV translates this in turn as “I assure you” But a completely unique use of amen by Jesus in the New Testament is recorded by the apostle John, whose Gospel shows us that Christ frequently doubled the word at the beginning of particularly important statements. In the King James Bible this is translated “Verily, verily,” in the ESV as “truly, truly,” and in the NIV “Very truly.” The doubling of amen was not only used by Jesus, however. In the early 1960’s part of a Hebrew legal document dating from the time of Jesus was found in which an individual declares “Amen, amen, ani lo ashem” meaning “Very truly, I am innocent.” It is possible, then, that Jesus borrowed this doubled form of amen from legal language of the day. But knowing that Jesus used this expression to signify important things he wanted to stress can help us see their importance in our own study of his words. The full list of occurrences of amen being doubled in John’s Gospel is: 1:51; 3:3, 5, 11; 5:19, 24-25; 6:26, 32, 47, 53; 8:34, 51, 58; 10:1, 7; 12:24; 13:16, 20, 21, 38; 14:12; 16:20, 23; and 21:18. It is interesting that while the New Testament writers often left untranslated certain Hebrew or Aramaic words such as abba, “father,” but immediately followed the word with a translation into Greek, they invariably left “amen” untranslated in its Hebrew form. This could possibly have been because they felt the word amen was known and understood by all their readers, but it is more likely that they knew that the word represented a range of meanings and they felt it better to simply include the word and let the reader or hearer consider the possibilities. If this is the case, we can draw a lesson from the fact. That small untranslated “amen” we read in our Bibles can mean more than just “may it be so.” We can often profitably think about what it most likely means in a given context or the intended force with which the expression was used. Finally, we should remember that “amen” certainly is not just a spiritual punctuation mark or a simple exclamation – wherever we use it we should think of it as a solemn affirmation that we are giving our personal guarantee that what was said is true! After training his twelve disciples and sending them out to preach the gospel, heal the sick, and cast out demons (Matthew 10:1–15; Mark 6:7–13; Luke 9:1–6), Jesus then selected another seventy disciples (seventy-two in some manuscripts) that he also sent out (Luke 10:1–24). While the twelve had been sent into Galilee, and told to avoid Gentile areas and Samaria, the seventy were not restricted in this way because they were sent ahead of Jesus to prepare people for his message (Luke 10:1).