1. They were attentive. Although Job and his friends were separated by considerable distances, they obviously stayed in touch to the extent that they knew that Job was suffering and could use their encouragement. We cannot help others if we fail to stay connected and are not attentive to their needs – whether they are friends, co-workers, aged family members, or others. Job’s friends were not so wrapped up in their own lives that they were disconnected from his; they were not too busy to stay in touch and see when he needed them.

2. They got involved. When they became aware of Job’s situation, his friends acted on the knowledge. They did not simply pray for Job – right and proper as that would be – they got involved to do what they could do directly. The friends doubtless sacrificed considerable time and energy in traveling to Job from other lands, and they apparently came at once rather than waiting for a convenient time, after the harvest, after the summer heat, or whatever.

3. They coordinated. Job 2:11 tells us that Job’s friends: “met together to go and sympathize with Job and comfort him,” or, as the ESV translates this verse: “They made an appointment together to come to show him sympathy and comfort him.” The three friends clearly coordinated with each other to help Job. We can learn from this by seeing the value of reaching out to let others know of a person’s need and by helping to coordinate visits or help for the individual from different people at different times.

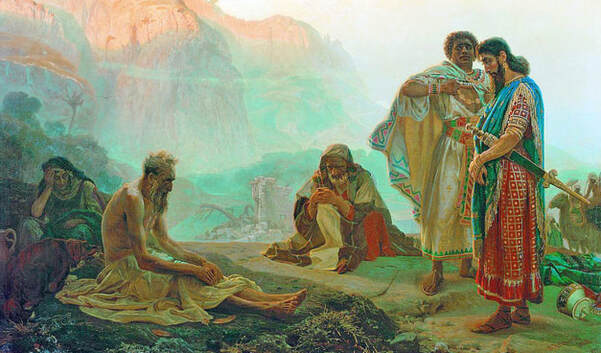

4. They reacted appropriately. The Bible tells us to “Mourn with those who mourn” (Romans 12:15), and we are told that when Job’s friends saw him “they began to weep aloud, and they tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads” (Job 2:12). Tearing one’s clothes and throwing dust or ashes on oneself was a sign of mourning in the ancient world, and this is what Job himself had done (Job 2:8). Jobs’ friends grieved deeply for him and they expressed their emotions in clear but appropriate ways that helped Job see they identified with him and his suffering.

5. They did best when they said less. The friends said nothing for seven days (2:13), and while they commiserated in silence the friends did no wrong. It was only once they began to comment on the situation that their mistaken assumptions of Job’s guilt made him even more miserable and eventually earned a rebuke from God himself. The friends’ statements about children who do wrong or who suffer for their parents’ wrongdoing (Job 5:4; 8:4; 21:19; etc.) were doubtless especially painful to Job who had just lost his own children (Job 1:5). Often, when people are suffering, we may try to say something to make the situation better or to offer encouragement – but what we say at such times can inadvertently appear to be arguing with the sufferer or hurt in other ways (Job 16:4; 19:2). Job’s friends showed there are times when it is better to say less and allow our physical presence to do most of the talking.

6. They stayed with Job. Despite their failings with words, Job’s friends stayed with him for at least seven days – it was no quick visit just to offer condolences. We may not always be able to give up extended periods of time to help others, but the principle of staying with the sufferer means doing things such as continuing to contact them, to see if they need help and to give them an opportunity to talk about their situation. We should notice that even when the friends stopped trying to speak to Job (Job 32:1), they did not leave for home – they stayed and continued sitting with him for some time.

These six lessons are simple enough, but applying them in our interaction with those who are suffering can make a great deal of difference.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed