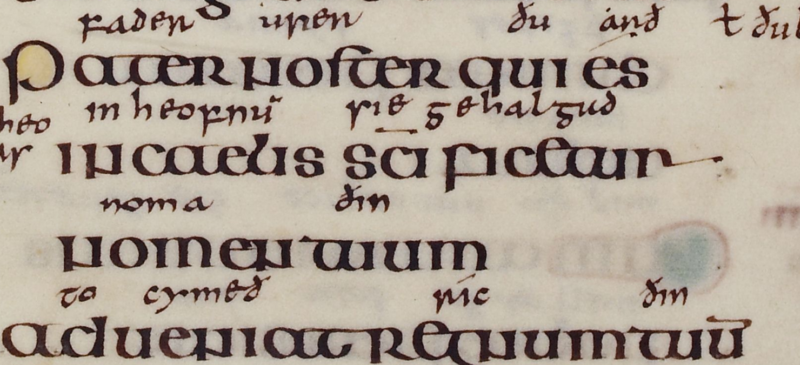

Thirteenth Century – Manuscript in the Library of Cambridge University:

Fader oure that art in heve, i-halgeed be thi nome, i-cume thi kinereiche, y-worthe thi wylle also is in hevene so be an erthe, oure iche-dayes-bred gif us today, and forgif us our gultes, also we forgifet oure gultare, and ne led ows nowth into fondingge, auth ales ows of harme.

Fifteenth Century – Manuscript in the Library of Oxford University:

Fader oure that art in heuene, halewed be thy name: thy kyngedom come to thee: thy wille be do in erthe as in heuen: oure eche dayes brede geue us to daye: and forgeue us oure dettes as we forgeue to oure dettoures: and lede us nogte into temptacion: bot delyver us from yvel.

Seventeenth Century – The King James Version of 1611:

Our father which art in heauen, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdome come. Thy will be done, in earth, as it is in heauen. Giue vs this day our daily bread. And forgiue vs our debts, as we forgiue our debters. And lead vs not into temptation, but deliuer vs from euill: For thine is the kingdome, and the power, and the glory, for euer.

Nineteenth Century – The English Revised Version:

Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, as in heaven, so on earth. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And bring us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.

Twenty-first Century – The Christian Standard Bible:

Our Father in heaven, your name be honored as holy. Your kingdom come. Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And do not bring us into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.

The differences between these instances of the Lord's Prayer become more noticeable the further we go back, of course, and considering that most of us know what the examples above say before we started to read them, we would probably agree that we would find it difficult to read a whole Bible of the thirteenth, fifteenth, or seventeenth centuries – even if it is in English.

While it may be interesting to see and realize the difficulty we would experience in reading a Bible in our own language unless it were of recent date, we can draw a useful lesson from this. Often, Christians think that the major work of Bible translations into other languages is essentially done. The Bible has, after all, been translated into over 700 languages, and the New Testament has been translated into well over 1,200 languages.

While it is true that this means the Bible has been translated into most important languages, it is still equally true that there are many thousands of dialects of these languages that still have no Bible translation. While we may think that local dialects are relatively unimportant – for instance, someone in the United States speaking a southern dialect can fairly easily understand someone using an Appalachian dialect – the differences in our dialects are relatively small.

But in many language groups the various dialects are just as, or even more, different than what we see in an English Bible of today and an English Bible of the thirteenth century – that you and I would find extremely difficult to read.

The moral of the story is simple. While a great deal of Bible translation work has been tirelessly accomplished by dedicated translators over the past century or so, there are many millions of people who still have no Bible in their own language, or only one in a related dialect that is very difficult for them to read. Understanding this situation can help us to pray more, and more intently, for still-needed translations, and to see the need to support the ongoing work of Bible translators in whatever way we can.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed