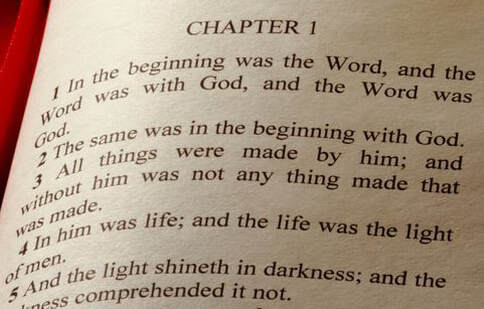

The opening paragraphs of the first chapter of the Gospel of John are one of the most majestic sections of the Bible. John’s eloquent prose seems unique in its presentation of Jesus as the “Word” of God. Yet despite its apparent uniqueness, John’s introductory chapter – like almost every other part of the New Testament – has its roots in the Old Testament and can only be fully appreciated when we see what those roots are.

It is often said that the Greek word logos – literally “word” – with which John begins his description of the preexistent Christ was used in ancient philosophy to signify the “reason” or underlying principle that created the universe. The Hellenistic Jewish thinker Philo of Alexandria who lived around the time of Christ used logos in this manner. However, the majority of John’s audience would not have known this philosophical usage, and they would have more likely understood the apostle’s description of Jesus as the “Word” in terms of their own Scriptures.

Jewish people would naturally have associated what John wrote with the opening statement of Genesis, that “In the beginning God made ...” (Genesis 1:1); but while Genesis stresses God’s action, John chooses to first stress the Son of God’s person and identity. Jewish readers (or hearers) would, however, also have recognized wider associations regarding John’s use of “Word.” They knew that “by the word of the Lord” (meaning by his command) “the heavens were made …” (Psalm 33:6), and they also knew that the Book of Proverbs personified that word or “Wisdom” as being active in the Creation of the world, and it is likely that most of John’s readers understood the personified “Word” in a similar manner. Some early Jewish commentators even pointed out that the Creation story of Genesis 1 used the expression “God said” ten times, seeing an analogy in this with the Ten Commandments which were called the aseret hadevarim – the “ten words” or “ten utterances.” God’s “word” could also mean, of course, all of God’s revelation to man. So John’s readers would have understood that he was characterizing Jesus as the personification and embodiment of God’s wisdom, law, and even all of God’s word – the entirety of the Scriptures.

But there are more specific connections between what John says in the introduction to his Gospel and the Hebrew Scriptures. The most significant are the parallels we find between John’s description of Jesus and the portrayal of God in the Book of Exodus. These connections are frequent and clear.

For example, just as Exodus tells us that God dwelt among his people in the tabernacle (Exodus 40:34), so John begins his description of Jesus by telling us that the Word dwelt (literally “tabernacled”) with humankind (John 1:14). Just as Exodus tells us that Moses beheld God’s glory (Exodus 33:18), so John makes a point of recording that the disciples and others beheld “…his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father…” (John 1:14). Just as Exodus tells us that God’s glory was full of graciousness (grace) and truth (Exodus 34:6 Holman, NKJV, etc.), so John goes on to say that Jesus was full of grace and truth (John 1:14).

Because the New Testament makes it clear that the preexistent Christ was the One who was with Israel in the wilderness (1 Corinthians 10:4), these connections may seem straightforward to us, but to John’s audience they were revelatory. The single verse John 1:14 alone would have suggested numerous parallels that devout Jews of that day would have recognized, but found amazing.

First century readers versed in the Hebrew Scriptures would have picked up other similarities between John’s record and that of Exodus. Most of the associations John makes within his first chapter are those expanding on the divine nature of Jesus. The Word is shown to be not just the promised “prophet like Moses,” but also very God himself. John does this by emphasizing not only Christ’s preexistence, but also his superior position to Moses. While Exodus tells us that the law was given through Moses (Exodus 34:29), John confirms that although “…the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (John 1:17). Jesus was not simply a prophet relaying the words of God, he was the One who was the Word and who himself exhibited the very nature of God.

This was John’s central point in comparing Jesus with the revelations of the Book of Exodus. Although Exodus stressed that no one could see all of God’s glory, and John confirmed the fact that “No one has ever seen God…” (John 1:18), John also stressed that in Jesus that glory was revealed: “…but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known” (John 1:18). Seeing this, we see John’s Gospel in a different light. The apostle who perhaps knew Jesus best did not just preface his Gospel with a grandiose but unconnected introduction. What John truly did, and what should inform our reading of his whole Gospel, was to show his readers from the outset that Jesus was everything that the “Word” of God was revealed to be – the personification of the wisdom, the law, and the very nature of God himself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed